The Big Picture

Films based on unsolved mysteries often aim for closure, but

Caché

intentionally leaves viewers in suspense.

Caché

delves deep into voyeurism, uncertainty, hidden guilt, and the impact of privacy invasion.

Director Michael Haneke challenges viewers with

Caché

, offering no clear answers to the film’s mysteries.

What’s the only thing people love more than a good mystery? Twist: it’s an unsolved mystery. Numerous urban legends are built around unsolved mysteries, an entire television show was built around exploring this concept, and entire subspaces of YouTube are devoted to uncovering as many known details about unsolved mysteries as possible. Movies don’t often explore unsolved mysteries, as cinematic storytelling tends to build towards catharsis, and unsolved mysteries are often anticlimactic, for obvious reasons.

Some films have tried exploring real-life unsolved mysteries, like Zodiac or Hollywoodland, to mixed results. Fictional films don’t fare as well, as most people who think up a mystery wouldn’t have the guts to not try and solve it. Then again, most people aren’t Michael Haneke, one of the world’s most provocative filmmakers. He gave a masterclass in not giving us the answers while still bringing us along for a deeply investing narrative with one of his best films, Caché.

Caché

Release Date February 17, 2006

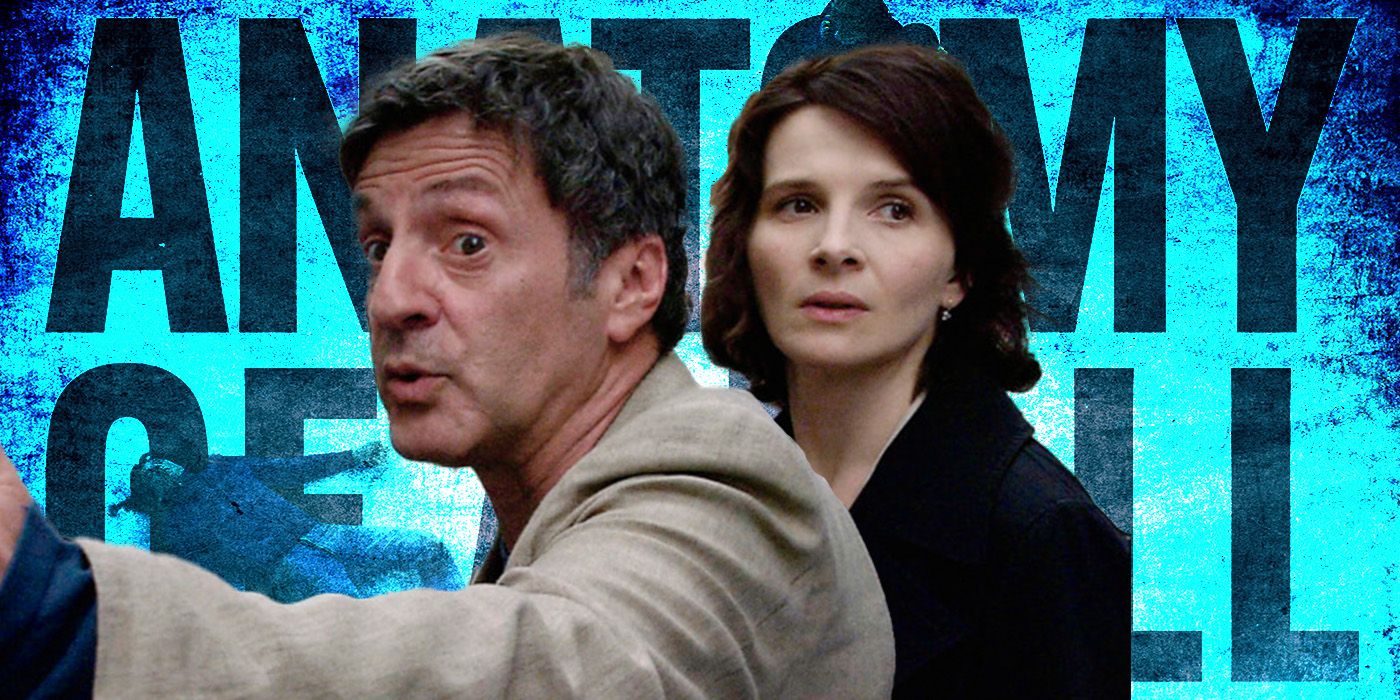

Cast Daniel Auteuil , Juliette Binoche , Maurice Bénichou , Annie Girardot , Bernard Le Coq , Walid Afkir

Runtime 117 minutes

Main Genre Drama

What Is ‘Caché’ About?

The Laurent family consists of literary criticism television show host, Georges (Daniel Auteuil), homemaker, Anne (Juliette Binoche), and their 12-year-old son, Pierrot (Lester Makedonsky). They’re the textbook affluent middle class French family, living a life of comfortable privilege without any real concerns in their life. That is, until a box appears on their front doorstep, containing videotapes and drawings, which are of violent acts committed on people, with red splashes of blood across the wounds. The videos are home video quality tapings of the Laurents’ daily activities, like going to their son’s soccer game. The police refuse to help, feeling that none of what they’re showing constitutes much of an actual threat, and the couple try and figure things out on their own. This is just the beginning of the falling dominoes in what becomes a human tragedy of uncomfortably intimate detail, despite the film’s mostly chilly proceedings.

From the opening shots, the film visually underlines the central theme of the power of voyeurism, playing out with a static shot of an apartment complex where life idles on for a solid two-and-a-half minutes. Once the credits are over, it’s revealed that this shot is one of the videotapes that Georges and Anne have found on their doorstep. This is a trick the film will do many times, giving us a seemingly ordinary establishing shot that will turn out to be one of the mysterious videotapes. Not only does it serve as a little jolt of misdirection to keep us on our toes, but it seeks to undermine our basic trust in the concept of taking images at face value.

Cinema is built on the notion of a shot giving us exactly what we need to know at any given time, so continuously changing the context of various shots instills distrust in us. For that matter, the film’s whole visual palette evokes a flatly lit digital handheld camera, minus the overly handheld quality. It makes us question the very foundation of what we’re watching, injecting a meta subtext of interrogating the very nature of engaging with cinema, itself.

‘Caché’ Shows the Power That Uncertainty Has Over Us

For the first half of the film, there are no solid suspects, save for one person. Though when one of the tapes reveals the estate that Georges grew up on as a child, he starts having dreams; it’s heavily implied that he hadn’t had these dreams until the videotapes showed up, indicating the presence of repressed memories that he’s tried to forget. These dreams fixate on a boy he knew named Majid, an Algerian orphan that Georges’ parents took in after they were killed in a racist massacre.

His parents were contemplating adopting Majid, but Georges didn’t want that, so he lied about Majid having tuberculosis, leading his parents to send Majid away. But did he actually lie? There’s a short sequence where we see a POV shot of someone walking through a dark house, leading up to us witnessing Majid with blood pouring out of his mouth, which is a symptom of tuberculosis. This is never given any context and never alluded to as a dream by Georges, and since every other dream sequence is clearly established as one, it casts doubt on whether Georges was actually telling the truth. The film has no clear answer, and that’s what makes it so mind-boggling.

This speaks to the most imperative thought on the film’s mind: how easily we’re shaken once we know we’re seen. In an age where privacy is ever-dwindling, it seems as if we’ve grown more comfortable being seen. However, that’s because—most of the time—we show things we want other people to see. But to have the parts of our life that we want kept private suddenly thrust in front of us is just one of the many existential nightmares we could face on a daily basis. Georges was perfectly content in his cushy life when no one was watching, but all it took was one suggestion of a disruption, and the dominoes in his mind fell swiftly.

In ‘Caché’, the Solution Is Not the Point of the MovieIf we were to play detective with what we end up knowing, it leaves only one real suspect, and even that suspect cannot be proven.Pierrot clearly has beef with his parents, even implying that Anne is having an affair at one point, but nothing connects him to any criminal activity. That leaves Majid’s adult son (Walid Afkir), who Georges suspects is the culprit, but the son denies it.This all might seem a bit sloppy from a writing perspective,but it was all part of Haneke’s plan to disrupt the audience’s sense of comfort and leave them unable to forget the film.This was a movie designed to tackle ideas likecolonialism, surveillance, and the nature of film as a medium, and Haneke felt it was “irresponsible” to tie all the bows up for the sake of the audience.

But then again, maybe he did secretly tie the bow right in front of our faces. The final scene of the film is a wide shot of Pierrot’s school entrance, and at the bottom left of the screen is Pierrot, who is approached by Majid’s son. Majid’s son is too old to be going to that school, and while we know that Pierrot has sometimes visited “friends,” we have no way of knowing who those friends are. It’s technically impossible that they would be anywhere near each other, unless they were simply two young men consoling themselves over their fathers’ shared trauma. Or perhaps, just maybe, they were conspiring with each other? To paraphrase Sherlock Holmes, if the impossible isn’t eliminated, then it could still be true.

Related Alfred Hitchcock’s Final Movie Is More Black Comedy Than Thriller Unsurprisingly, the Master of Suspense had a shockingly dark sense of humor.

Michael Haneke is—above all else—a cynic who’s deeply fixated on the ways in which humankind can tear itself apart under the guise of social niceties. Having gained notoriety for films like Funny Games and The Piano Teacher, he specialized in looking at how even the things that are meant to bring us together (like art and sexuality) can become tools for our destruction. Caché works primarily for its focus on how guilt for even unintentional actions can rip someone apart on the inside.

On a more galaxy brain level, it skewers the audience’s demand for the safety blanket of security, forcing us to confront the notion that even cinema, just like life, is not truly at the whim of the audience’s need for answers. Even though the answer feels like it’s right in front of our faces, by the rules of cinema, we cannot actually solve it. What good is a smoking gun if the person who fired it might not even exist?

Caché is available to watch on Tubi in the U.S.

Watch on Tubi